On November 2nd, the doctors told my father he had days to live. At once, my siblings and I, spread far and wide, converged upon our childhood home like pilgrims to a spiritual birthplace, and we watched our father die.

There were many of us there: my mother, my two sisters, my sister-in-law, my brother, my two brothers-in-law, my three nieces, my mother’s mother, two dogs, two cats, countless family friends, community members, neighbors, relatives, old frat brothers, former coworkers, apple trees, lingering tomato plants, blades of grass, clouds, rain, sunshine, a gibbous moon, light, darkness, and myself.

For five days, we laughed and cried. We ate and drank. We watched sports and ran errands. Our dad was with us, laughing and eating too, and carrying on as best he could. Over five days, he would laugh a little less and eat a little less, and carrying on became harder and harder. On the fifth day of our vigil, he could carry on no longer, and passed away in the mid-afternoon, surrounded by his immediate family holding hands and saying goodbye.

For some reason, leading up to his passing, I kept telling myself it was selfish to grieve. This wasn’t my death. This was his. I get to continue on. I get to taste chocolate and see leaves turn yellow and fall to the ground. I get to laugh and cry and hold hands and see smiles and wipe tears. I get to run and feel the air fill my lungs and feel my heart beat faster when I’m excited and slower when I’m at peace. I get to see the mystery of tomorrow answered when it becomes today.

He won’t get to do that anymore. And so, my first grief was for him.

And though I thought that to grieve is selfish, I accepted grieving for him, because he was not done living, and a soul who perishes with unfinished living is a tragic thing indeed.

But the dead need not concern themselves with life. That is the business of the bereaved.

And so, my second grief was for us: his family and friends, who now get to continue living without his presence, for without him, the world is a little dimmer, and a little less wise. And for us, a little lonelier.

And though I thought that to grieve is selfish, I accepted grieving for us, because we must continue to live without our father and husband and friend and teacher, and being deprived of him is a tragic thing indeed.

And yet, I also experienced a third grief: a grief for me. An unacceptable grief. My selfish grief. My grief of shame.

Allow me to share:

Days before he died, I scratched out in a notebook:

I’m afraid.

I’m a coward.

I can’t handle this.

I am weak.

You see, I wanted so deeply to be there for my father and my family when he passed. I wanted so very deeply for him to be surrounded by his loved ones. I wanted so very deeply to be there for my sisters and my brother and my mother. But I was terrified that my cowardice would take over, and that I would, at that most essential moment, flee. I was almost sure I would flee my family when they would need me the most.

And so I was grieving my cowardice.

I can’t even watch people die on television. How can I expect myself to watch my father die in real life? What wretched weakness will betrayed itself in that pivotal moment when I should stand strong for him and for us?

Strength. What does strength mean in that moment? Does strength mean standing there, staring death in the face, and telling your brother, “It’s okay”? Does strength mean sustaining the composure needed to be able to wipe away others’ tears?

Here’s how it happened:

The moment came on the afternoon of November 7th, and despite expecting it for five days, it was unexpected. My mom said “now,” from his room, and the siblings and I looked up confused. Then she yelled, “NOW!” and we understood. We all rushed to my father’s side, and heard his final breaths. We held onto each other as we wished him goodbye. I couldn’t see his face. It almost seemed like a dress rehearsal. It wasn’t real. We had been waiting for this for five days; why would it happen now of all moments?

I saw myself there, as if I wasn’t there at all, but rather watching myself from outside of me, and I was confused that I had not fled, considering I was so certain I would. Was I doing my duty? Was I there for my family? It seemed that, yes, I was, but something was too easy. I wasn’t upset enough. Maybe it’s because I wasn’t there at all, but here, watching myself be there from outside of myself.

But then, a moment after he passed, I walked over to my brother to hug him, and I turned and looked at my father’s face — the face my brother had been watching as life left it.

He was dead.

I snapped back into myself, and the dam burst.

All the emotion I had been holding, the three griefs, the fear, the cowardice, they all came rushing back, and my strength, whatever strength I thought I had, vanished. I couldn’t handle it. I couldn’t handle any of it, and I did exactly what I thought I would do:

I fled.

I ran into my parents’ bedroom, and I wailed hysterically, sobbing uncontrollably on the floor. I had never known I was capable of such a powerful emotion. It was the strongest feeling I had ever felt. The moment is a raw fog. People came in to comfort me, to make sure I was okay. Eventually I held myself up by the bedpost and regained my composure.

And then… it was over. I was fine.

Later that evening, my family commented on my hysteria, even jokingly. For some reason, I was embarrassed.

But then, when I left the following day, my mom hugged me, and she said, “Thank you for your grief.”

And then I understood: I was never meant to be strong for my family. I was meant to be weak. My role in this was never going to include wiping the tears of my sisters. My role was to sob uncontrollably on the floor, for it was through my violent release of grief that my family was better able to access their own, to experience what they needed to experience. Maybe it was that I should be weak so that my family could be strong and comfort me. Maybe through my grief could we access the profound magnitude of the moment. Maybe my grief helped bring us closer together. I’m not sure what it was or how it needed to be, but now in hindsight, it couldn’t have been any other way.

It has been several weeks now. I am doing well. I often think about how wonderful it has been to cry — how beautiful it is that we get to experience such a vast, dynamic emotional world. Sometimes I think it’s easy to fall into a numb ennui about our existence — our lives are streamlined from birth to death, designed by formulae, our interests and passions commodified for our convenience, our inner lives analyzed and written into self-help books. It’s really easy to live life somewhere in the mundane middle on the scale of emotional experiences. That I have had this grief means that I have had the fortune of joy. That I sob means that I have valued something or someone. It means that my life can engage with the sublime. It means that I can finally understand what it’s like to experience the loss of a loved one, so that I may be there for others who will. Because we all will, as it seems it should be in this world.

Grief has taught me a lot this year:

Don’t grow too attached to the future.

Respect the past; its sum is your present.

Weakness can be essential. Do not mistake it for cowardice.

It’s okay to be sad. Maybe even preferred.

Fear is yearning for strength.

Grief is love.

Sure, you can disagree with these platitudes, but these lessons aren’t yours, they’re mine; they’re the ones I need to learn. I need to learn that I must be free to live passionately, to live true to my heart, lest I be too careful, lest I make the mistake of never really living at all, lest I clutch foolishly to a plan that was never mine. I should be so lucky as to grieve so again someday.

dhood memories are filled with moments strolling through that garden, picking and eating fruit off trees or tomatoes off the vine. Even now, as I enter the deeper part of my adulthood, I continue to stroll through my parents’ garden to which my father continues to diligently tend, as a way of communing with the fabric of my past.

dhood memories are filled with moments strolling through that garden, picking and eating fruit off trees or tomatoes off the vine. Even now, as I enter the deeper part of my adulthood, I continue to stroll through my parents’ garden to which my father continues to diligently tend, as a way of communing with the fabric of my past.

Look at it. The coffee is black. You can almost taste the roast with your eyes. It’s poured into a porcelain cup, the way black coffee should be, as to not taste the paper. I imagine the black coffee pouring over the whiteness of the porcelain, hot on my tongue, but not scalding. It has hints of caramel and chocolate.

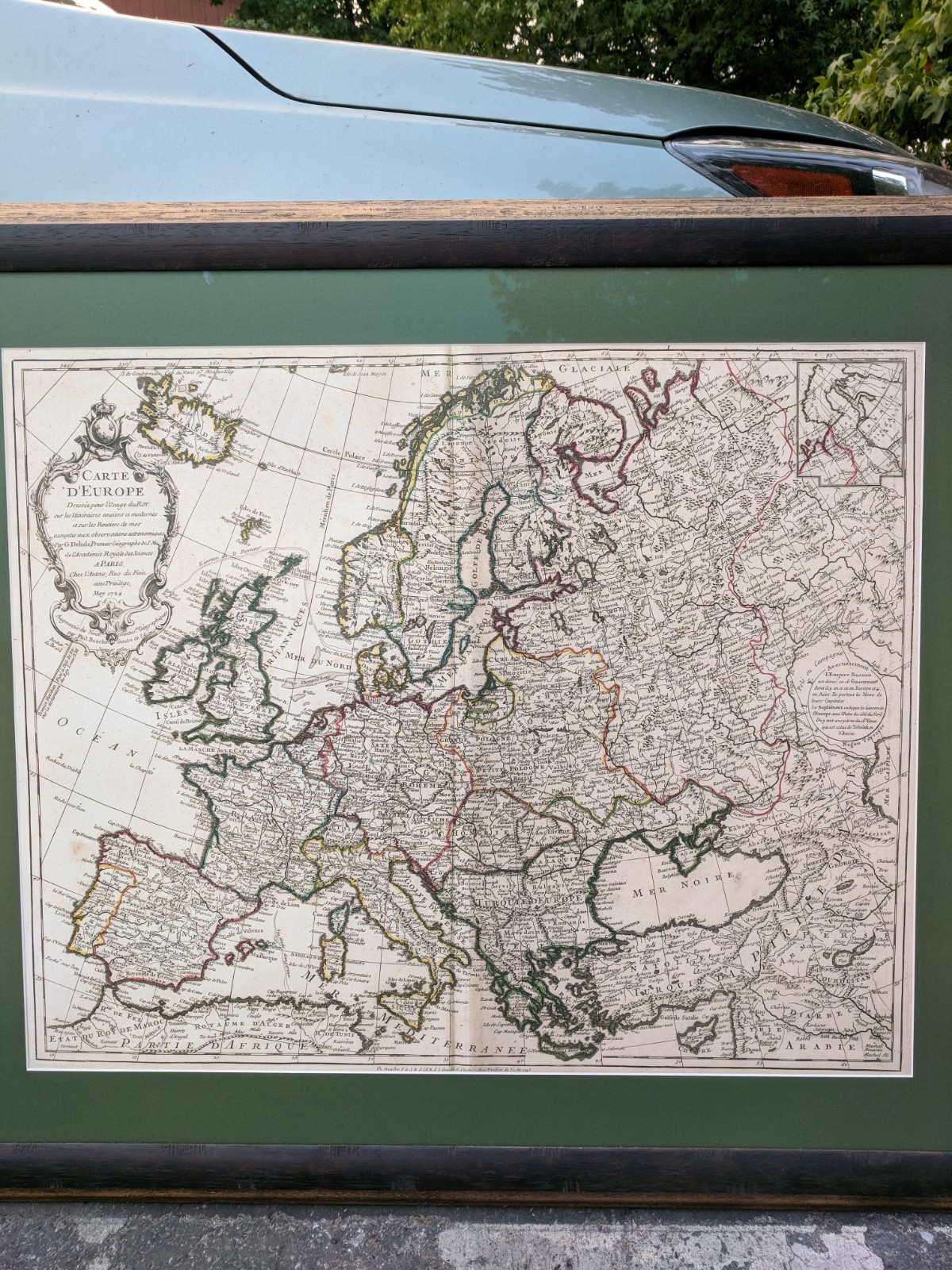

Look at it. The coffee is black. You can almost taste the roast with your eyes. It’s poured into a porcelain cup, the way black coffee should be, as to not taste the paper. I imagine the black coffee pouring over the whiteness of the porcelain, hot on my tongue, but not scalding. It has hints of caramel and chocolate. You see, it was an old map of Europe in my grandfather’s house that got me interested in European history when I was younger. Each nation has a story. Each border has a conflict. When you look at how maps shift, you’re looking at how civilizations clashed, how people moved, and how ideas changed the geography of humankind. This map led to many of my academic pursuits today, and my uncle’s map hearkened back to it.

You see, it was an old map of Europe in my grandfather’s house that got me interested in European history when I was younger. Each nation has a story. Each border has a conflict. When you look at how maps shift, you’re looking at how civilizations clashed, how people moved, and how ideas changed the geography of humankind. This map led to many of my academic pursuits today, and my uncle’s map hearkened back to it. In 2014, I moved back to my parents’ place after Grad School, and slowly began to decay, emotionally and psychologically. My parents are loving, and home was comforting, but returning home is a blow to the personal narrative that life moves forward, and that the past nine years hadn’t been just a dreamy waste of nonsense and futility.

In 2014, I moved back to my parents’ place after Grad School, and slowly began to decay, emotionally and psychologically. My parents are loving, and home was comforting, but returning home is a blow to the personal narrative that life moves forward, and that the past nine years hadn’t been just a dreamy waste of nonsense and futility.

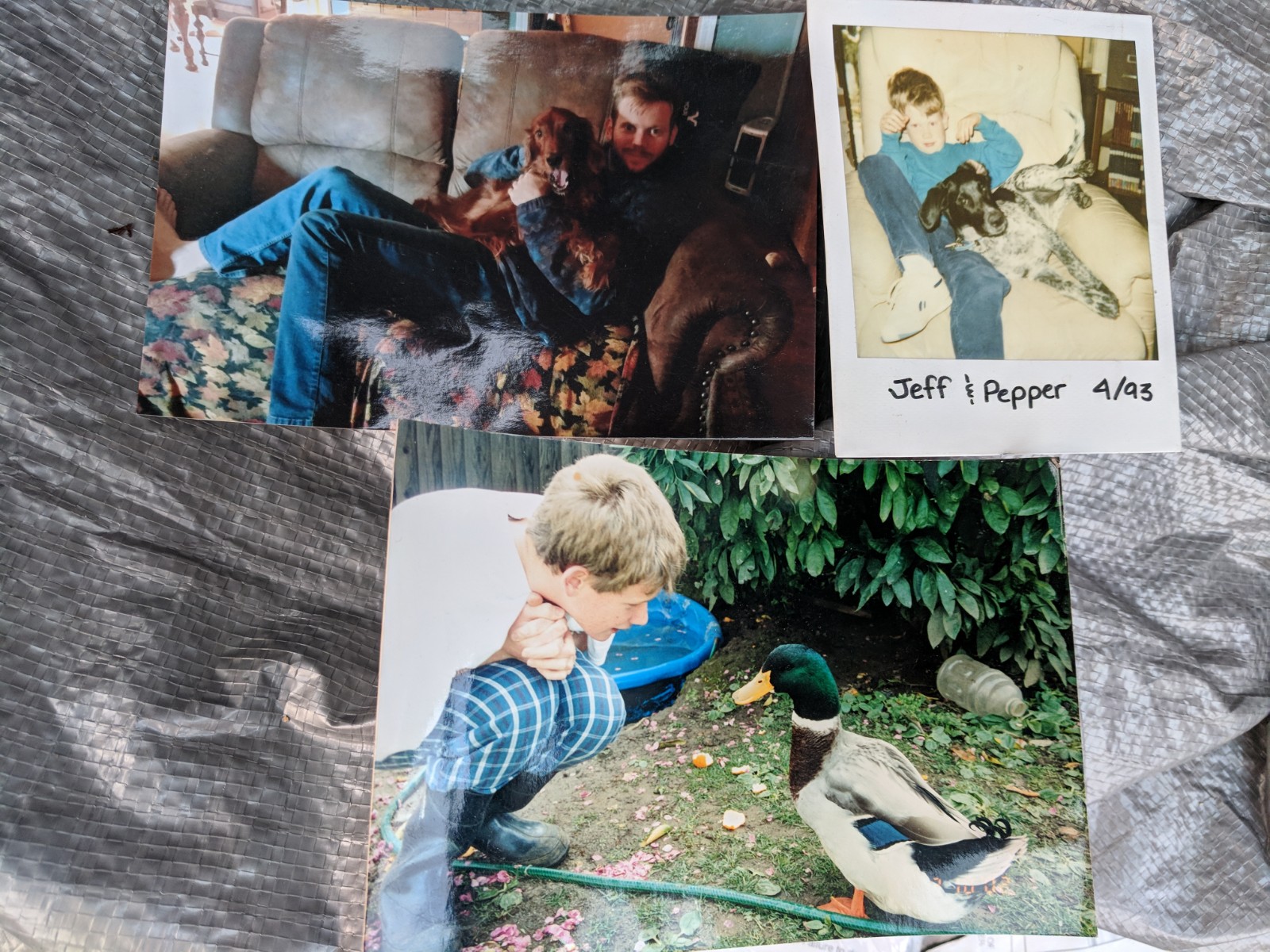

People have been giving me duck-related items since I was in the third grade, when I had a pet duck. Over twenty years later, I’m still receiving duck gifts. It hit a peak over a year ago when I hosted a family in my apartment for several months. The kids, knowing I had an affinity for ducks and also knowing I really didn’t need any more duck paraphernalia, took it upon themselves to play a long and drawn-out prank. They began hiding, one by one, ducks in my house.

People have been giving me duck-related items since I was in the third grade, when I had a pet duck. Over twenty years later, I’m still receiving duck gifts. It hit a peak over a year ago when I hosted a family in my apartment for several months. The kids, knowing I had an affinity for ducks and also knowing I really didn’t need any more duck paraphernalia, took it upon themselves to play a long and drawn-out prank. They began hiding, one by one, ducks in my house. My brother and I have traded off possession of the violin. Neither of us are violinists, and yet we’re both drawn to it enough to ask each other for it from time to time. It just so happens that eventually I became a music teacher, and so it was due time for me to learn violin. That is when I laid claim to it, and in a way it became mine.

My brother and I have traded off possession of the violin. Neither of us are violinists, and yet we’re both drawn to it enough to ask each other for it from time to time. It just so happens that eventually I became a music teacher, and so it was due time for me to learn violin. That is when I laid claim to it, and in a way it became mine.